Introduction

The PI planning event provides a great pattern for filling a backlog, but its all too easy for teams to fail to capitalise on their great beginning with effective ongoing backlog refinement.

How do we get from those hastily scrawled post-it’s to fully articulated stories in user-voice form with comprehensive acceptance criteria? Given that many Release Trains move from “all-waterfall” to “all-agile” via a one-week quick-start, a solid set of starter pattern practices is a useful tool to help them accelerate their journey. This article focuses on the evolution of an individual backlog item. A follow-up article will cover techniques for managing the overall backlog.

How do we get from those hastily scrawled post-it’s to fully articulated stories in user-voice form with comprehensive acceptance criteria? Given that many Release Trains move from “all-waterfall” to “all-agile” via a one-week quick-start, a solid set of starter pattern practices is a useful tool to help them accelerate their journey. This article focuses on the evolution of an individual backlog item. A follow-up article will cover techniques for managing the overall backlog.

Whose job is it?

In my early agile days, I learnt that a story was a token for an ongoing conversation between the team and their customer. The important thing was the conversation, some details of which needed to be preserved by writing them down.Unfortunately, all too many people interpret user stories as “the new form of requirements”. They want to know who’s responsible. Does the Product Owner write the detailed stories and hand them to the team? Does the BA work with the Product Owner to do so? These are depressingly common anti-patterns, and our first mission is to avoid them. Story evolution is a collaborative activity regardless of the stage of maturity of the story, and I always start teams off with the mantra that nobody writes alone.

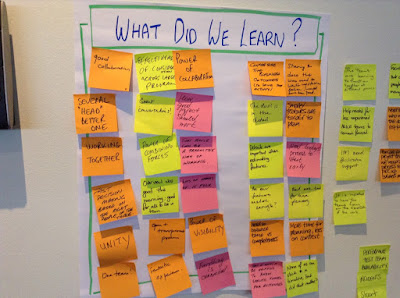

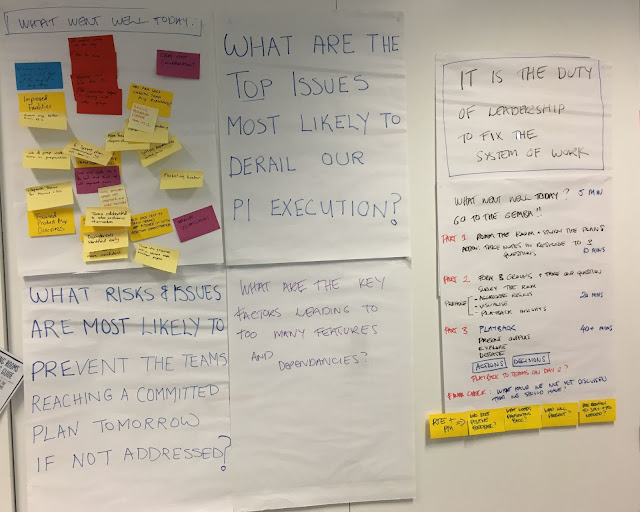

PI planning sets the scene perfectly. Each team starts with an empty backlog, and over the course of the breakouts works with their product owner, product manager and subject matter experts to explore their features – recording the results of the exploration as a set of backlog items.

So we’ve started well by having a conversation and recording a set of tokens for the details of the conversation on post-its – how do we keep that good pattern going after we leave PI planning?

Does it always have to be the whole team?

Having the whole team involved in an activity is an expensive (and not always productive) exercise. While the fully shared context is desirable, it’s not always necessary or valuable. Involving the whole team in workshops in their early life for the shared learning is great, but most evolve reasonably rapidly to some variation of Jeff Patton’s “3 Amigos” or triad approach. Jeff describes a triad as “Product Owner, BA and developer” (the 3 amigos). I don’t tend to be quite as prescriptive – what I’m looking for is diversity of input, so I tend to recommend “one of each discipline”. The most common format for this is “Product Owner, BA, Dev, Tester” or “Product Owner, UX, Dev, Tester”.

One caveat to this is to make sure triad memberships rotate to spread knowledge. The Product Owner will be a constant, and if the team has a BA they’ll also usually be relatively constant but what we don’t want is a pattern where it’s always the “dev lead and lead tester”. The more the understanding of the problem domain is spread around the team, the better the outcome!

One caveat to this is to make sure triad memberships rotate to spread knowledge. The Product Owner will be a constant, and if the team has a BA they’ll also usually be relatively constant but what we don’t want is a pattern where it’s always the “dev lead and lead tester”. The more the understanding of the problem domain is spread around the team, the better the outcome!

Moving to User Voice Form

Teams rarely generate great user voice form stories during PI planning. There just isn’t time. If we’re lucky, they might have done so for their first sprint but most of the backlog will consist of items like “pay by the month”.It’s highly tempting to detail someone to go off and “upgrade the stories”, but we miss something. The point of user-voice-form is to help us to look through the eyes of our users. The discussion as we identify roles and “so that” reasons enriches our understanding of what we’re trying to accomplish. The last thing we want is for the team to miss out on that conversation.

So, the team should set a goal of having a “rolling 3 sprints” of backlog that’s been refined to user voice form and moving as rapidly as possible to achieving this after PI planning. It’s a pretty rapid activity, so usually not all that hard to achieve with a set of well-facilitated one hour workshops. There’s a good reason for this. As we move to user voice form, we flush new insights – often in the form of missed stories or missed complexity. It’s good to learn about this early in the PI.

Establishing a Definition of Ready

Nothing destroys a sprint like a poorly defined set of stories entering the gate. All teams are taught to establish a definition of done, but I’m a huge personal fan of a “Definition of Ready”. This defines the set of conditions a story must meet in order to be accepted into Sprint Planning.

Exactly how much or how little is required to “be ready” is highly dependent on context. In highly regulated environments this often includes signoffs from legal and risk on acceptance tests. These are folks not renowned for moving fast - discovering you need an approval from legal in the middle of the sprint is a recipe for an unfinished story and missed sprint goals.

A good question to seed the definition is “what are you likely to discover in the middle of the story that might take more than a couple of days to get an answer to?”. This then forms the guidelines for key things to answer when preparing the story. The rule of thumb I’ve found quite useful is getting the acceptance tests to “80% lockdown”. There are always some questions that will be revealed once developers crack the story open, but the “80% rule” enables an approach where “if the expectation just changed by more than the 20% we allowed for the new detail its fuel for another story and a future sprint”.

My strong recommendation to all teams is “provide all the detail in your acceptance tests”. The temptation to elaborate the story by filling in tables of business rules and bullet point acceptance criteria before developing acceptance tests just leads to waste and redundancy. Using techniques like Specification by Example or BDD workshops take you straight to acceptance tests and provide very useful ways of exploring the problem domain collaboratively.

Employing a definition of ready as well as a definition of done establishes a two-way contract between the team and product owner:

Exactly how much or how little is required to “be ready” is highly dependent on context. In highly regulated environments this often includes signoffs from legal and risk on acceptance tests. These are folks not renowned for moving fast - discovering you need an approval from legal in the middle of the sprint is a recipe for an unfinished story and missed sprint goals.

A good question to seed the definition is “what are you likely to discover in the middle of the story that might take more than a couple of days to get an answer to?”. This then forms the guidelines for key things to answer when preparing the story. The rule of thumb I’ve found quite useful is getting the acceptance tests to “80% lockdown”. There are always some questions that will be revealed once developers crack the story open, but the “80% rule” enables an approach where “if the expectation just changed by more than the 20% we allowed for the new detail its fuel for another story and a future sprint”.

My strong recommendation to all teams is “provide all the detail in your acceptance tests”. The temptation to elaborate the story by filling in tables of business rules and bullet point acceptance criteria before developing acceptance tests just leads to waste and redundancy. Using techniques like Specification by Example or BDD workshops take you straight to acceptance tests and provide very useful ways of exploring the problem domain collaboratively.

Employing a definition of ready as well as a definition of done establishes a two-way contract between the team and product owner:

- The product owner take accountability (with the support of the team) for ensuring that stories meet the Definition of Ready before being brought to sprint planning.

- The team takes accountability (with the support of the product owner) for ensuring that stories meet the Definition of Done before being reported as complete.

The “Next Sprint” Kanban

Story detail should leverage the law of the last responsible moment. We want it neither too early nor too late. My encouragement is to go no deeper than a user-voice form version of the story until the sprint before it is due to play.Each sprint thus has a dual purpose. Complete the current sprint’s committed stories and flesh out the next sprint’s stories to meet the definition of ready. The first ingredient in doing so is to introduce the “Next Sprint Kanban” to visually manage this journey.

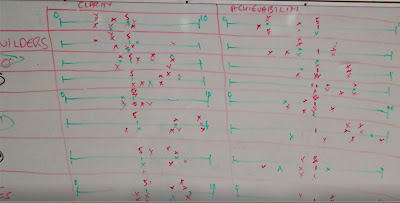

The board illustrated below was from a high assurance environment, where acceptance tests were detailed in the “Specifying” state, then stories were sent off to legal and risk in the “sign-off” state prior to hitting “Ready”.

Figure 1 - Team Aliens: A slightly different approach to

visualizing next sprint preparation and a helping hand from Dilbert

Specification Workshops

- Put them on cadence. Two-three 1-hour sessions per week will usually feed a team pretty well. Scheduling them straight after standup is great as you can use the standup to organise who (whole team or designated amigos) will participate.

- Don’t produce polished detail, your focus is shared context. Use a whiteboard (preferably in the team area to allow for osmotic communication) and lots of photos as you explore to keep the pace moving and energy up. Word-smithing can be done either solo or by a pair (Product Owner/Tester works well) as followup.

- The Product Owner needs to order and do some pre-thinking on the stories both to help them identify any subject matter experts or other stakeholders who might need to be involved and to assist the team in identifying appropriate amigos to participate.

Story Splitting

Good backlogs are, of course, iceberg shaped. As Jeff Patton puts it so eloquently “stories are like cheese, best sliced fresh”. Story splitting will tend to occur naturally as a by-product of user-voice-form workshops and specification workshops. Whatever you do, don’t bury yourself in deep story hierarchies. One layer is good. “Here is my feature, and here are the stories that represent it”. When you split a story, tear up the original and replace it with the newly identified split stories.